Interview Survey of Korean Workers Mobilized in Wartime at the Jōban Coal Field and Their Families

Interview Survey of Korean Workers Mobilized in Wartime at the Jōban Coal Field and Their Families

Kōji Tatsuta

- Author

- Kōji Tatsuta

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Interview Survey of Korean Workers Mobilized in Wartime at the Jōban Coal Field and Their Families

Kōji Tatsuta

- Introduction

In this paper, I roughly summarize my three-year journey in South Korea visiting Korean workers mobilized in wartime —a journey which I must say has just begun.

I conducted three surveys, each of roughly a month in duration. Half of the duration each journey was spent on the actual interviews, the remainder on preparation and organization in Seoul. I would like to start by expressing my deep gratitude for the generous assistance that I received from many people along the way, including the (below, ) in Seoul, and outside Seoul, administrative officers in local administration divisions as well as officers in charge of town and township family registers. My thanks go above all to those former mobilized workers who, despite their advanced age, participated in interviews that were also sometimes conducted in my clumsy Korean if no interpreter was available. There might be things that I have misheard, but I have set down reporting on these interviews in the hope of at least setting the stage for future studies. I believe that this is the first time that interviews have been conducted with those Korean mobilized workers wartime in the Jōban Coal Field who returned to Korea.

- Survey Outline

- Survey organizaer: (Chair: Katsuhisa Ajima)

- Survey personnel: Kōji Tatsuta (first and second surveys), and Kōji Tatsuta (third survey)

- Survey periods and areas:

First survey:

May 2005; Hamyang County (South Gyeongsang), Hoengseong County (Gangwon Province), Uiseong County and Dalseong County (North Gyeongsang Province),Jecheon County (North Chungcheong Province)

Second survey:

May 2007; Jecheon County (North Chungcheong Province), Gangwon Province

Third survey:

June 2008; North and South Chungcheong Provinces, Muju County (North Jeolla Province), Gangwon Province

- Survey content

First survey: Preliminary survey (seeking interviewees and meeting with families)

Equipped with a list of victims, I visited Hamyang County in South Gyeongsang, Hoengseong County in Gangwon, and Uiseong County in North Gyeongsang, where death rate was relatively high, and other places thanks to local officers from the Verification Commission, officers in charge of family registers, and people who offered their cooperation on a voluntary basis, I was able to meet for the first time with survivors from the Jōban Coal Field. I was also able to meet with three family members of deceased victims and learn about their feelings.

It was just around that time that agreement had been reached at the Koizumi-Roh Moo-hyun talks on repatriation of the remains of deceased Koreans. Korean media awareness was consequently high, and the Hankyoreh and Seoul Shinmun newspapers both covered this issue, which made it easier to get people to cooperate in my surveys.

Second survey: Jecheon County and Gangwon Province (narrower range of regions and themes)

After a year away from the project, I got hold of materials on the Jecheon at the Dainippon Nakoso Coal Mine and helped particularly by such materials as the names of those accused of being involved in “group violence” as well as the , I went out to Jecheon for some focused survey work. Gangwon Province was the largest source of worker mobilization for Jōban. In Hoengseong County, I conducted relatively detailed interviews with one survivor whom I had contacted in the first survey, and another survivor to whom I had not spoken before. I also made some progress with interviewing the families of the deceased, but only managed to cover five counties. The family register survey of victims that I conducted by mail produced four responses to 35 requests, which I was then able to use in my third survey.

Third survey: North and South Chungcheong Provinces and Gangwon Provinces (strengthening ties with local institutions)

This time, I asked in advance for the cooperation of the Third Survey Division of the Verification Commission, Cheongju City and Okcheon Town and also added another person to the survey team so that we could conduct interviews by a team of two, resulting in a certain amount of progress. The Third Survey Division managed to introduce me to nine survivors, and I was able to conduct basic interviews with five of these. Focusing on resistance struggles by wartime mobilization, I also conducted a search based on the names listed as the accused in the ruling on the incident of group violence that occurred at the Furukawa Yoshima Coal Mine in 1943 and managed to conduct interviews with their families. The Okcheon Town Office also kindly introduced me to three family members of deceased workers whom I was able to interview. I made some progress too with investigating the issue of remains and damage from aftereffects.

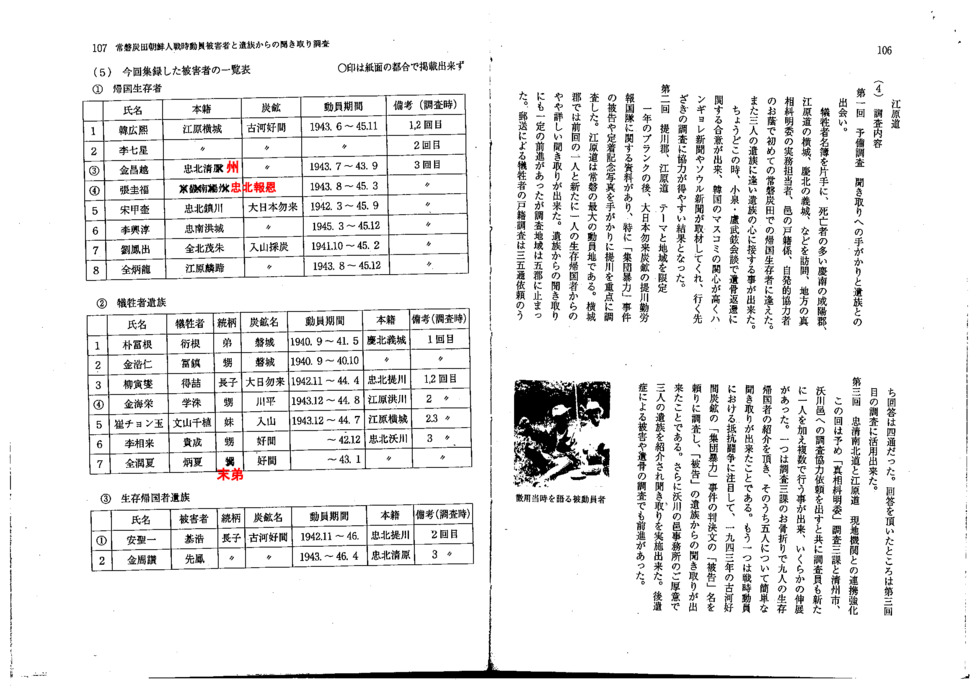

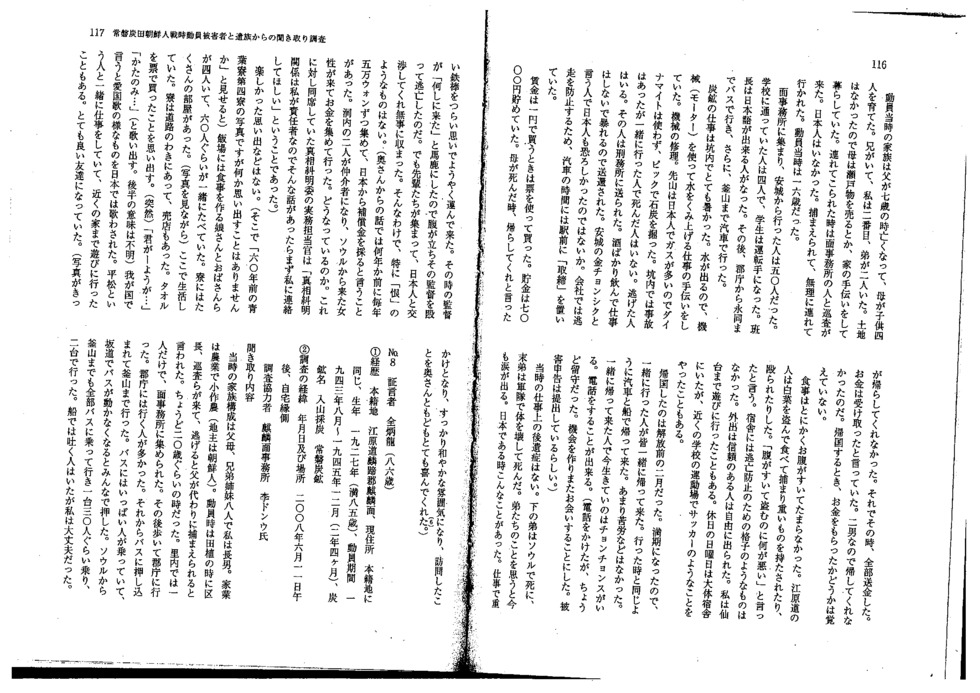

[CAPTION] Former mobilized workers talk about their experience

- List of victims interviewed (Numbers in brackets indicate those who I could not include in this paper.)

(1) Survivors who returned to Korea

|

|

Name |

Registered domicile |

Mine |

Mobilization period |

Survey round |

|

1 |

Han Gwanghui |

Hoengseong County, Gangwon |

Furukawa Yoshima |

06/1943-11/1945 |

1st & 2nd |

|

2 |

Lee Chilsong |

Hoengseong County, Gangwon |

Furukawa Yoshima |

06/1943-11/1945 |

2nd |

|

(3) |

Kim Changwol |

Cheongju City, North Chungcheong |

Furukawa Yoshima |

07/1943-09/1943 |

3rd |

|

(4) |

Jang Gyubok |

Boeun County, North Chungcheong |

Furukawa Yoshima |

08/1943-03/1945 |

3rd |

|

5 |

Song Gabgyu |

Jincheon County, North Chungcheong |

Dainippon Nakoso |

03/1942-09/1945 |

3rd |

|

6 |

Lee Heungsun |

Hongseong County, South Chungcheong |

Dainippon Nakoso |

03/1945-12/1945 |

3rd |

|

7 |

Ryu Bongchul |

Muju County, North Jeolla |

Iriyama |

10/1941-02/1945 |

3rd |

|

8 |

Byeongyong |

Inje County, Gangwon |

Iriyama |

08/1943-12/1945 |

3rd |

(2) Victims’ families

|

|

Name |

Victim |

Relation |

Mine |

Mobilizationperiod |

Registered domicile |

Survey round |

|

1 |

Park Boogeun |

Park Yeongeun |

Younger brother |

Iwaki |

09/1940-05/1941 |

Uiseong, North Gyeongsang |

1st |

|

2 |

Kim Hoin

|

Kim Boojin |

Nephew |

Iwaki |

09/1940-10/1940 |

Uiseong, North Gyeongsang |

1st |

|

3 |

Ryu Inseob |

Ryu Deokcheol |

Eldest child |

Dainippon Nakoso |

11/1942-04/1944 |

Jecheon Nth Chungcheong |

1st & 2nd |

|

(4) |

Kim Haeyong |

Kim Haksoo |

Nephew |

Kawahira |

12/1943-08/1944 |

Hongcheon, Gangwon |

2nd |

|

5 |

Choe Cheonok |

Fumiyama Senshoku |

Younger sister |

Iriyama |

12/1943-07/1944 |

Hoengseong, Gangwon |

2nd & 3rd |

|

6 |

Lee Sangrae |

Lee Kwisong |

Nephew |

Yoshima |

-12/1942 |

Okcheon, Nth Chungcheong |

3rd |

|

7 |

Jeon Yunha |

Jeon Byeongha |

Youngest brother |

Yoshima |

-01/1943 |

Okcheon, Nth Chungcheong |

3rd |

(3) Families of survivors, who later died in South Korea

|

|

Name |

Mobilized workers |

Relation |

Mine |

Mobilization period |

Registered domicile |

Survey round |

|

(1) |

An Seongil |

An Giho |

Eldest child |

Furukawa Yoshima |

11/1942-1946 |

Jecheon Nth Chungcheong |

2nd |

|

2 |

Kim Juchan |

Kim Seonbong |

Eldest child |

Furukawa Yoshima |

1943-04/1946 |

Cheongwon, Nth Chungcheong |

3rd |

III. Interviews with survivors who returned to Korea

- Interviewee: Han Gwanghui (Japanese name: )

(1) Background

Registered domicile: Ucheon Township, Hoengseong County, Gangwon Province

Current address: Same as above

Born: 1925

Mobilization period: June 1943-January 1946

Name of mine: Furukawa Yoshima Coal Mine Company Ltd.

(2) Interview background

Dates:

1st interview May 3, 2005

2nd interview: May 30, 2007

Place: Interviewee’s home in Ucheon Township

Cooperation: Administrative official from Hoengseong County Local Administration Division

General background: The first person whom I interviewed in Korea. This report is compiled by myself based on both the first and second interviews.

Interview content

At the time when I was mobilized, my family comprised my father, my older brother, me, my wife, and a child who had just turned one. My wife was 21 years old. We were sharecroppers. In June 1943, I had come from letting water into rice paddies of 8 majigi (majigi: unit used for tillage area in Korea, 1 majigi means area to plant 1 doe of seeds) and had gone to bed. I was woken by several people including the secretary from Township standing in front of my house and at the rear entrance. People from my hamlet and the next one over were calling out “This is the home of Han, isn’t it” and “Han, come out.” Because it was raining heavily, I was taken to an inn in a nearby hamlet. There were five people from my hamlet. After that, we had to walk to Hoengseong and were gathered at the County office. One person was chosen as a leader for a group of 10 people and given an armband to wear. We were all given grey working clothes. We stayed the night at an inn, but a number of people escaped out the windows. Of the 95 men from Hoengseong, many escaped along the way, so we were 45 when we arrived.

The supervisor spoke very good Korean. His name was Shirota, and I couldn’t tell whether he was Japanese or Korean. I clearly remember the name of the village secretary who was part of the forced mobilization, as well as the names of collaborators from the hamlet. We travelled from Hoengseong to Wonju by truck, and from there on to Pusan by train. In Pusan, we boarded a ship so big that I thought it was a house. Rough waves tossed us around and I suffered from terrible seasickness. From Shimonoseki we boarded a train and went to Yoshima.

There was a river in front of the mine lodgings. There were almost no farmhouses in the vicinity, except for a large one by a bamboo grove. I was in a dormitory with men from Pyeongchang. We would cross the river and walk to the mine entrance. Two men from my hamlet went to another mine over the hill. Yoshima was warm even in winter, and even when it snowed, the snow vanished as soon as it touched the ground.

The first week at the mine was spent learning about the various jobs, which included practicing using a drill that used air pressure to dig holes, digging mine shafts using dynamite, using picks to dig coal, and putting in and taking out machinery. My job was to dig coal. One man was too tall to work underground, so his job was to carry the food. Koreans weren’t given jobs in the mess hall because it was thought that they would steal food. We went into the mines in teams of four, each headed by a sakiyama (skilled front-line miner). Genba (foreman) went around supervising. Day and night shifts were alternated on a weekly basis, and everyone would put a stamp by their number every morning before starting work. If you were sick and couldn’t work, your food ration was halved. On Saturdays, ratios were halved even for men going off to work. If you faked illness to avoid work, they put you face down and beat you on the buttocks. When there was a power cut in the mine or the machine that pumped out water broke down, the mine would fill with water, and a number of men died as a result. There was a man called Ryeo Gwangseok who got sick and died. He was cremated, and when I went home, I took his remains with me to pass on to the county office. I also bumped into manki, the thing that we put coal in and raised and lowered [probably, a tram] and hurt my back shortly after I started working at the mine. So, I couldn’t work for three years after I got home. I got some treatment at the hospital, but they didn’t let you stay in hospital for an injury that slight. My food was of course halved.

There were around 45 men from Hoengseong and around 50 from Pyeongchang in the Yamanobō dormitory. In the Matsuzaka dormitory, there were some men from Pyeongan Province, but we didn’t visit each other. Each tatami room slept five people. An amount of food measured according to the number of people to be fed was piled up in a large wooden tub and served by Japanese women from the dispensing window. The food was rice mixed with barley, and sometimes there were potatoes and seafood as well. They made us lunchboxes for lunch, but sometimes we would eat all our lunch before lunchtime and take along an empty lunchbox, so because we were hungry, we would pay five yen to the men selling black market food and eat that. We smoked finely shredded tobacco in Japanese smoking pipes. There was no alcohol, so anyone who wanted to drink had to go to Tairamachi.

We were paid once a month, but only received a little at a time regardless of how much we earned. The remainder we had to put into savings. Now and then, I sent 300-500 yen home. Some men used up all their savings on having fun. I sent two or three letters home, written for me by someone else. On holidays, we would go to orchards and sneak apples and Japanese pears. The farmer would be furious if he caught us. Sometimes we went to the market and bought horse meat to eat. Sometimes we bought watered-down alcohol to drink. When planes came, the Japanese went down the mines to hide, but we Koreans just watched, because we thought that Koreans wouldn’t be attacked.

We weren’t punished unless we did something wrong. There was no way we could resist. I didn’t hear anything from people who were there before me about Koreans engaging in big riots, like going on strike about the rice ration. [In response to a question] If you didn’t do anything bad, you weren’t treated particularly harshly.

On August 15, the Emperor came on the radio to give an announcement, saying that the Greater East Asia War was suspended for the meantime. On the 16th, we went to Tairamachi and bought some cloth on which we drew the Taegeuk (supreme ultimate) flag of Korea, and everyone said that we should go out and shout a manse (Korean form of cheer meaning ten thousands years). We went to a bamboo grove and cut down all the bamboo to put up the flag on the end of bamboo to hang. One or two months later, the American forces directed us to Niigata to wait for a boat, but after days and then weeks, the boat still didn’t come, so we went to Nagasaki. There was no boat in Nagasaki either, so after waiting some days, it was decided that we would get on a cargo carrier. I used the whole 400 yen that I had saved. Of the six of us who came home together, everyone except Mr. Lee has died. Since I’ve been back, I’ve made my livelihood through farming. When I injured my finger, Japanese guys said I should have it cut off, but I said no way. They’re a bit malformed now, but they’re okay.

[What I want to say to the Japanese and the people of Iwaki] I guess I did go to Japan, but there’s nothing that can be done about it now. There’s been no apology, and Japan should acknowledge the facts. I’d like to go to Japan again. I remember the cherry blossoms blooming.

- Lee Chilseong (fictitious name)

(1) Background

Registered domicile: Hoengseong Town, Hoengseong County, Gangwon Province

Current address: Same as above

Born: 1923

Mobilization period: June 1943-January 1946

Name of mine: Furukawa Yoshima Coal Mine Company Ltd.

(2) Interview background

Date: May 30, 2007

Place: Interviewee’s home

Cooperation: Hoengseong County local administration division officials

General background: Mr. Lee was not happy with an interview format, so the interview took the form of a conversation. A fictitious name was therefore used.

Interview content

After my third conscription notice arrived, I thought I had better go so as not to cause problems for my family. When the village labor officer came out with the third notice around June 1943, it was pouring with rain. Six people were conscripted with me, and one was chosen to head our group. Now only Mr. W and I are the only ones still alive. I was farming with my parents and my two brothers, and I’d been married just over four months. There were around 47 men down at the county office. A Korean from Japan was in charge, and we went around the back of the country office to pray at the shrine and sing something like our national anthem. Then we were loaded on to a truck and went to Wonju by truck. [According to Mr. Lee’s wife, she had to plant rice that day, and she couldn’t go to see Mr. Lee off, because she was so scared of her mother-in-law. She saw her husband waving from the new road, a sight that still remains in her head today.] The mobilization route was Wonju (train) à Seoul (train) à Pusan (ship) à Shimonoseki (train) à Tokyo à Yoshima Coal Mine, Fukushima Prefecture. We stayed one night in an inn in Pusan, and they fed us rice when we got to Japan. Four people escaped from the inn in Pusan, which was discovered on departure when they counted the number of people.

Yoshima Coal Mine where I was sent was about eight kilometers from the provincial office [Tairamachi?], and you had to go eight to 12 kilometers to get to the sea. There were no classes of worker, just engineers who were known as sakiyama. About half the workers were Japanese and the other half Korean, with the Koreans including people from Gyeongsang Provinces and other places. There were other mines around, but I don’t know what they were called.

At the beginning, my job was the pipe work for underground water. It didn’t pay much, so I asked to let me dig coal instead, which pleased the Japanese. My plan at the time was to earn a lot of money and escape. We worked in teams of five. The sakiyama had overall responsibility, and inside the mine we used machinery to make holes where we placed explosives to blast the rock. Then we used a scoop to put the coal in wagons to take away. Going into a new shaft is not that dangerous, but when you keep digging and have carved out several lines, you have to bring the coal out from there, and that’s where there’s a high danger of collapse. When I was there, the whole sixth layer had just dug out and we were starting on the seventh. The shaft had been weakened from all the digging and was very likely to collapse. When a shaft collapsed, we would say “yama ga kita” (“the mountain (mine) has come”).

However, our mine was the one called model mine, and there were no major accidents. The adjutant would always come to our morning and evening assemblies and tell us that such-and-such mine had collapsed so we should be careful, or warn us to be particularly careful of the wagons and the cable that pulled up the coal, that kind of thing. We were fed well enough. They mostly served us bowls of millet rice with lots of barley through it. It was better than the food that peasants ate at home. We also got tobacco and alcohol, but I can’t remember if these were deducted from the month’s wages. Because it was a model mine, we weren’t beaten or treated inhumanely. Sometimes someone of high ranks would come to check the food or watch us at work.

I had heard that if you escaped and were caught, you would be half-killed, so that wasn’t an option. If you escaped, the best way would be to act like a gentleman with a lot of money, but if you looked rough, you would get caught sooner or later. I learned enough Japanese to converse. Japanese is easy.

We gathered for work at seven and had an hour-long morning assembly before we started work. We worked a full eight hours, swapping between day and night shifts every week. If you were told to dig a certain number of wagon loads per day, you were expected to achieve that. I earned around 40 yen a month. Sometimes I would send 20 yen home at a time, and sometimes I put aside the money that I would need to escape. Sometimes I sent letters. We were controlled so that we couldn’t interact with people from other mines.

Sunday was a holiday, so we relaxed in a place like a park. We needed to get a permission slip to go anywhere. We bought alcohol and drank it. Even if we went out, we couldn’t go more than eight kilometers, and because you didn’t know who would catch you, escape was unthinkable. Even if we went to the shops, there was nothing to buy. There was something made of seaweed that was like muk [a Korean food usually made from mung beans with a jelly-like consistency] that I bought and ate sometimes.

We were freed on August 15. The Japanese would never say they had lost, just that there was a cessation of hostilities. During the month before we were freed, planes would come and it was hard to sleep. Even after the 15th, we were told to work, and kept working for another month or so. Then we went to Niigata at the direction of the US forces, and waited for a boat. When I left the mine, I was given 600 yen, but I lent someone 300 yen so I only had 300 yen with me. A major and an interpreter from the US forces came and told us to wait a few days, but we waited for about 40. No ship came, so we made an eight-day train journey to Nagasaki. The roads had been damaged by bombing and we couldn’t travel very fast. Even in Nagasaki, there was no ship straight away, so we had to wait for a while. When a cargo ship came along, we boarded that. It wasn’t a ferry, but rather had cars and cargo on board. The sea was rough so the boat couldn’t go very fast, and I got seasick, throwing up from the bottom of my stomach every time the ship lurched. I suffered much more on the journey home than working at the mine. Everyone from Hoengseong was the same. When we got to Gunsan, we ate dinner then got on the train to Seoul. We walked as far as Cheongnyangni to get on a train, arriving in Wonju that evening. Then we walked to Hoengseong [January 1946]. When I got to Hoengseong, a relative came and told me that I should not to go home because my family had typhoid. However, having survived wartime Japan, it seemed bad-mannered not to go to see my parents just because I was afraid of getting sick, so I went home anyway. They had suffered the worst of it by then and were on the road to recovery, so I didn’t catch it.

When I got home, my daughter was three. I’ve continued to farm since then. Occasinally, when I ran into one of the people who had sent me off on conscription, he was terrified that I would beat him. I would ask him whether he had done that to me because he wanted to, and told him not to worry it. Back in the mine, when I was propping up the beams that supported the shaft, I got jammed between two wagons and was helped by a fellow worker to finally escape. My back was badly bruised and I spent a month in hospital, but there were no aftereffects. H who went over to Japan with me was digging holes and setting explosives down the mine when there was an explosion. He couldn’t get out of the way, so the whole front of his body was burned black. One man from Hoengseong Town who was at the mine got heart disease and died. Everyone said that I should be the one hold a funeral ceremony for him, so we cremated him and buried him in the public cemetery at the temple. My brother-in-law was also in Japan, going before me. He was at a mine in Fukushima Prefecture, but I don’t know what the mine was called. I couldn’t speak much Japanese but sometimes I would go to see him. He was really good at Japanese and said that he had earned lots of money.

- Song Gabgyu (86 years old)

(1) Background

Registered domicile: Bangseung Township, Jincheon County, North Chungcheong Province (formerly Gwanghyewon Township)

Current address: Same as above

Born: 1922

Mobilization period: March 1942-End of September 1945

Name of mine: Dainippon Nakoso Coal Mine

(2) Interview background

Date and place: June 3, 2008

Place: Interviewee’s home

Cooperation: Jincheon County local administration division official Ro Chanho

Interview content

The coal mine I was sent to was called Fukushimaken.Iwakinokori Nakosomachi Dainippon Tanko[i] for my family at the time when I was mobilized, my mother and father had died early on, so things were hard. I lived with my uncle and cousins. I sold wood for a living. I hadn’t finished school, so I didn’t understand Japanese, which made life difficult.

There were 50 of us from this township, Bangseung Village, and 50 from other townships, so a total of 100.[ii] How we got to the Nakoso mine was that we gathered first at the township office, then went by car to Cheon, then by train to Pusan. From Pusan we went by ship to Shimonoseki, then by train to Ueno. Then we arrived in Nakoso. It was March when we arrived, so it wasn’t cold. I didn’t see any cherry blossoms.

Our hanba [Translator’s note: simple housing for workers, usually consisting of a mess hall and a dormitory] was called Nakamura [Chunchon] Hanba. There were a number of buildings, with the mess hall right in the middle. They fed us rice with a lot of potatoes and millet, and the soup wasn’t fit for human consumption. The side dishes included sardines and other fish. Pickled daikon radish was on the table every day. We worked every day, and all I can remember is going backwards and forwards between the mine and the hanba. Even on holidays, I didn’t go anywhere. I don’t know about anything else.

At the mine, I mostly loaded coal and helped with the blasting. I was really busy every day. Every time we blasted, an enormous cloud of dust would go up, and we would work in the middle of it. Some people died in gas explosions. Wages were about 15 yen a month. I got someone to send about 15 yen home for me. When I got back I asked if the money had arrived, and apparently it had.

If you did something wrong, you were dragged off to the office and beaten. I remember that the particularly harsh labor supervisors were called Hiruta and Matsueda, and also Satō. I can’t really pick them even in photographs. There were some events thing like riots. Sometimes we didn’t do as we were told and just refused.

After liberation, I went home together with seven older men. In the same way as we came, we went through Ueno then by train to Shimonoseki, and by train from Pusan back to Cheonan. Tokyo had been flattened. We left in August and got home in September, so the journey was about a month. I didn’t take any money with me. Together we finally got home. The first month I was back, I was sick and couldn’t work. After that, I leased some land and began farming. The Korean War broke out, and things got really hard. I got married when I was 27. My wife died 37 years ago. Now I live with my son, his wife, and my grandchildren. My grandchildren are at school now.

Maybe as an aftereffect of working in the mine, my respiratory tract isn’t so good and I cough, so I go to the doctor about that. Sometimes I have coughing fits at night, too. I go to the hospital in Seoul once a month. It all costs money. [The Interviewee had a number of coughing fits during the interview too.]

These days I don’t have anything to do with the Japanese. I don’t even hold a grudge. [?] When the Verification Commission conducted a survey of damage, I received a certificate, but it doesn’t mean anything. Could you ask if they could send some compensation or something?[iii]

- Lee Heungsun (81 years old)

Japanese name: Yasuhira Kōsai

(1) Background

Registered domicile: Seobu Township, Hongseong County, South Chungcheong Province

Current address: Same as above

Born: 1927

Mobilization period: January 11, 1945-December 1945

Name of mine: Dainippon Nakoso Coal Mine

(2) Interview background

Date: Morning, June 9, 2008

Place: Path between rice paddies near the interviewee’s home

Cooperation: Oh Jeongseon, local officer from the Verification Commission’s Hoengseong County branch

Interview content:

My family was originally my parents and four older brothers, but at the time that I was conscripted to Japan, my eldest brother had died, so there was just me and my two older brothers left.[iv]

At the time that I was mobilized, I was doing a bit of farming, and also had to find pine roots and make oil out of them. We had a little bit of our own land and the rest was tenant land. The landowner was Korean, but at the time, two-thirds of the county’s landowners were Japanese, and the head of the township, the principal of the elementary school, and the local policemen were all Japanese. No conscription orders were issued at the time of mobilization. The district head just came to get people and told them that they were conscripted. If you didn’t go, you were beaten. There were 50 or 60 people from Hoengseong. There were two captains. There were three men together from Osari Village. This was on January 8.

[When shown photographs and asked if he was in them][v] That’s me standing next to the lamppost wearing traditional Korean dress. This tall man is Hoshino Eikan from Kyonsan Township (20 years old), who was a great guy. I went over to Japan in standard Korean dress. I wasn’t given working clothes. I got to the mine by walking from the township to Hoengseong, going by train to Pusan, getting on to a ferry, then getting on a train again. I can’t remember whether we were given rice balls along the way. The name and address of the mine were Hanayama Dormitory, Dainippon Coal Mine, Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture.

Because I was young (17), my job was to load and carry the coal. The sakiyama were engineers responsible for laying the dynamite, which was a really difficult job. Some Koreans also became sakiyama. The daily production target was four wagons and 30 manki [not sure what this means, but perhaps tram?]. There were two shifts, swapped on a weekly basis.

We got no wages, or only a tiny wage. I didn’t send money home. The hardest thing was feeling starved. We ate three meals: morning, noon, and evening. The noon meal was a lunchbox with pickled daikon radish on the side. There was hardly anything in the lunchbox. I was under age, so I didn’t get a tobacco or alcohol ration, but occasionally I got wine. There was no alcohol or tobacco to be bought even if you had money. I sent a letter home once, but the work was so hard that I had no energy to send more. I wrote the letter myself in Korean. I could speak some basic Japanese. In the hanba, Captain Yoshida often struck. There were around 500 Koreans in the hanba, maybe more. The Korean hanba had a mess hall and a bathroom. There might have been three or four blocks? The water in the bath went muddy and completely black.

Of the men who came with me from Heongseong, I don’t know whether Kim Songhwan died, but there were definitely others who did. The dead were cremated. I didn’t know that there was a list at the temple. A lot of people died from bad lungs. Air raid sirens would sound, and sometimes I slept with my shoes on.

After liberation, we all went home together. Since some people had escaped, wwe were around 20 when we came home, out of the original number of 57 or 58. We went by train from Pusan to Heongseong then walked to Osari Village. Even after liberation, I kept working until December. I don’t know whether some people went home immediately after liberation.

After I got home, I was taken by an army corps for the Korean War and had a really hard time. My back is bent because I injured it while I was at the mine and a steel beam fell on me from above. Even though I was injured, no one called a doctor and I couldn’t take time off work. The supervisor, who was also a Korean, was really strict, and he struck me and sent me out to work. [The Interviewee showed us his back, which still had a big scar.] My youngest son has some physical issues and can’t work, so I’m still working now.

I do bear a “han (grudge)”, against the Japanese. When the Korean government conducted a survey, they said they would give me 30,000 won, but they didn’t. They do these surveys, but we don’t get any compensation. [According to the Verification Commission’s local officer, some fraudulent behavior went on in Heongseong as well around compensation.]

- Ryu Bongchul (83 years old)

Japanese name: Kirishima Kuro

(1) Interviewee background

Registered domicile: Anseong Township, Muju County, North Jeolla Province

Current address: Same as above

Born: 1925

Mobilization period: October 1941-February 1945 (three years and four months)

Name of mine: Iriyama Coal Mine, Jōban Coal Mine

(2) Interview background

Date: June 17, 2008

Place: Interviewee’s home

Cooperation: Local Verification Commission officer for Muju County Eom Seungseob and Muju County Tourism Division Interpreter Machiyo Kondō

Interview content

When I was mobilized, my father had died when I was seven, so my mother was bringing up four children. There was my older brother, me second, then my two younger brothers. We didn’t have any land, so my mother sold crockery and did housework for people. Someone from the township office and a constable came to take me away. There were no Japanese. I was captured and forced to go. I was 16 at the time.

We gathered at the township office. There were 50 people from Anseong. Four were still at school. Students became drivers. Those who spoke Japanese became unit leaders. We went by bus from the county office to Yeongdong (county), then to Pusan by train.

I worked inside the mine and it was very hot. My job was to help scoop out the water that seeped up in the mine using a machine and to repair the machine. The sakiyama were Japanese, and because there was a lot of gas we couldn’t use dynamite but had to dig out the coal with picks. There were accidents in the mine, but no one I went with from home died. Someone escaped. He was sent to prison. He was sent home because he drank a lot, did no work, and brawled. His name was Kim Chongsik and he was from Anseong; I think the Japanese were afraid of him too. To stop us escaping, the company posted overseers in front of the stations around the time of every train departure.

My wages were one yen, and when I bought something, I used tickets. I saved 7000 yen. When my mother died, I asked them to send me home, but they wouldn’t. So I sent all my money instead. Apparently, it arrived safely. They wouldn’t let me go home because I was the second son. I can’t remember if I got any money when I finally returned home.

When it came to food, I was always desperately hungry. A guy from Gangwon stole a Chinese cabbage and ate it. They caught him and made him carry heavy things and beat him. Apparently, he asked them what was so wrong about stealing when he was hungry. At our lodgings, there were no bars or anything to stop us escaping. People that were trusted were allowed to go out as they liked. I even went to Sendai. Sunday was our day off, and usually I just stayed at the lodgings, but sometimes I played something like soccer at the local school grounds.

I went home two months before liberation along with all the people I came with, because our term was up. We came home by train and by boat again, just like when we went to Japan. It wasn’t too bad. Of the people that went to Japan and came home with me, Jung Cheongsoo is the only one still alive. I can talk to him by phone. [We rang but he happened to be out just then, so we decided to arrange an opportunity to meet him another time. Apparently, he has submitted a claim.]

I don’t have any aftereffects from mine work. My younger brother died in Seoul, and my youngest brother got sick in the army and died. When I think about my younger brothers, it brings tears to my eyes even now. When I was in Japan, there was this incident. I had finally managed to shift a heavy steel bars, and the supervisor ridiculed me for struggling. It made me mad, so I hit him and ran away. But the older men got together and negotiated with the Japanese, so nothing happened to me. That’s why I don’t have any particular han (grudge) against the Japanese today. [According to his wife, some years ago, someone started collecting 50,000 won every year (from the former mobilized workers) in preparation for trying to get compensation from Japan. Two people from the neighborhood mediated, and a woman came from Seoul to collect the money. Ryu’s wife asked what was happening with that. The Verification Commission officer with me said that he was in charge of those matters, so if she heard something, she should come to him.]

I don’t have any good memories of my time at the mine. [When shown a photograph of Aoba No. 4 Dormitory 60 years ago and asked if he remembered anything,] at the hanba, there were four women, some younger and some middle-aged, who made the food, and about 60 of us ate together. There were lots of rooms in the dormitory. [Looking at the photograph,] I lived here. The dormitory was on the side of a road, and there were also shops. I remember using a ticket to buy a towel. [Suddenly] Kimigaayouga … katanomi [he starts singing the Japanese national anthem. The latter half was incomprehensible.] In Japan, we had to sing something like what at home we call songs of patriotism. I worked with a guy called Hiramatsu, and I even went over to his house to hang out. He became a really close friend. [After the photographs came out, the atmosphere suddenly became very relaxed, and both the interviewee and his wife were very glad that we had visited.[vi]

- Jeon Byeongryong (86 years old)

(1) Interviewee background

Registered domicile: Girin Township, Inje County, Gangwon Province

Current address: Same as above

Born: 1927 (85 years old)

Mobilization period: August 1943-December 1945 (two years and four months)

Name of mine: Iriyama Coal Mine, Jōban Coal Mine

(2) Interview background

Date: Afternoon, June 11, 2008

Place: Verandah of interviewee’s home

Cooperation: Girin Township official Lee Dongoo

Interview content

My family at the time was my parents and eight children. I was the eldest son. We farmed on leased land (the landowner was Korean). It was rice planting time when the district head and the local constable came around; they told me that if I escaped, my father would be taken instead. I was about 20 at the time. I was the only person from my village. We were gathered at the township office, and then walked to the county office. A lot of people went to the county office. We were then pushed into buses and went to Pusan. The buses were so full that on uphill stretches they stopped moving and we had to get out and push. The whole journey from Seoul to Pusan was by bus. There were two buses, with about 30 men on each. On the boat, some people threw up, but I was alright. Some people escaped from the place that we stayed. Then we went on the train; the mine was close to the station. The mine was called the Jōban Coal Mine. Fukushimaken.Iwakinokori, , Aoba. It wasn’t the Iriyama Coal Mine.[vii] My job in the mine was to dig the coal and then use a scoop to load it into carts. It was almost too hot to work. We worked, sometimes soaked in water. We didn’t wear clothes; we were naked. The sakiyama would drill a hole and blast the rock. Once while I was working, a coal wagon ran into my back and I was badly injured. I wasn’t allowed to go to hospital; I just took a few days off and then I was sent back to work. [The Interviewee showed us his back.]

There were three shifts, and we changed once a week.

I received no wages. Not enough money to buy a cup of makkoli [Translator’s note: Korean rice wine]. I don’t know if anyone told us about the wages when we were mobilized. I heard that we were going to a coal mine. We heard that recruiting had cost a lot of money. The dormitory master said that he would remit my wages, but when I went home, I asked my family and they said that they had received nothing.

I can’t remember what we called the dormitory master. We had to call all the Japanese in the dormitory sensei [Translator’s note: literally “teacher,” used as a term of respect]. Around 300 people apparently lived in each dormitory. When we went to work, we were divided into units of five to seven people. We received hardly any food. We got three meals, but lunch was a lunchbox with hardly anything in it. Potatoes, sweet potatoes, barley and other grains were mixed in with rice. I drank water to fill my stomach. There were tobacco and alcohol rations, but I was small and not very productive, so I didn’t get any. On holidays, I remember sumo contests and other events. A lot of people escaped and were caught. If they were caught, they weren’t just beaten, but beaten almost to death, and if they passed out, water was thrown on them and then they were beaten again. Two Japanese called Saitō and Eguchi were particularly bad. The Korean unit leaders didn’t beat people. I didn’t fight back. If I was told to do this, I did this; if I was told to do that, I did that.

I kept working long after liberation. Eventually we got together and started pressing our demands. We even held meetings, but American troops came from Onahama and stopped them. There were American troops in Taira but I never met them. The mine was deep in the mountains, so it was never bombed.

I can’t really remember if the journey home was by train. It was terrible because there was no food. I don’t remember any of the details of the trip. I got off the boat at Incheon and I don’t remember what happened after that. From Chuncheon I walked home. It was December in the old calender when I arrived. There was nothing good about the entire time that I was mobilizeed. Since I’ve got back, there hasn’t been as much as an acknowledgement. I feel hugely aggrieved. Later, I went off to the Korean War. Many people died. They were conscripts, conscripted soldiers. Some people came back, but many died.

- Interviews with family members of victims who died in Japan

- Interviewee Park Booguen (sixth younger brother of victim Yeongeun)

(1) Background

Address: Bian Township, Uiseong County,

Born: 1936 (nine years old at the time of liberation, and a second-year student at elementary school)

Occupation: After graduating from high school in Daegu, worked at the township offices until retirement.

Other: Lives with his wife. The main branch of the family had a lot of land. Second and sixth sons did not inherit any. The whole main branch of the family has died out.

(2) Background of the victim

Registered domicile: Bian Township, Uiseong County, Gangwon Province

Born: January 19, 1921

Died: May 1941

Name of mine: Iwaki Coal Mine

Cause of death: Crushed to death (at age 20)

(3) Interview background

Date: May 7, 2005

Place: Interviewee’s home (Family register confirmed the previous day at the town office)

Cooperation: Song Taegyeong and his wife Mutsuko

Interview content

When my brother was mobilized, I was only around five years old, so I had no idea what was going on. I didn’t hear that he had been crushed to death. He didn’t have any land either, so [possibly in response to a recruiting drive] he went to Japan to earn some money. He had graduated from futsu gakko (meaning “normal school,” elementary school for Korean children under the rule of Japan), so he should have been able to speak Japanese. The main branch of the family lives at No. 401 Dongburi Village, a little bit away from here. My brother was 20 years old and unmarried with no children, so there is no one to look after his grave. Now I don’t even know where his grave is. Uncle on the maternal side went to fetch his remains and apparently came home with his ashes. My father Honggu passed away in 1955, and my mother also died 30 years ago. Currently, my uncle is in Daegu. Another uncle who graduated from Waseda University lives in Japan, and my niece is in Osaka. My wife was born in Osaka. My nephews in Daegu were going to register a complaint as part of the investigation into the truth which the government is currently conducting, but there weren’t any documents, so they gave up. The Japanese government is supposed to have paid compensation in the negotiations that took place when the Park Chung-hee administration was in power. If we make demands again at this late stage, people would think that we just lacked common sense. So, there’s really no point in making demands. I haven’t heard about anyone from around here getting 300,000 won in compensation back then. Who went off from this village with my second elder brother? There was Kim Okseok. He died three years ago, but his wife is still living here by herself. The house is close by, so you should go and see her. He was like brother to me. He didn’t talk much about Japan. What I’d like to say to the Japanese people is that Korea is a brother nation and Japan’s closest neighbor, so we should clear the slate for the past as soon as possible and get along with each other. [After the interview, as a keepsake, I sent Park a piece of slag mixed with coal brought home from the slagheap at Iwaki. Fighting down emotion, Park said that his father had died of mental illness thinking about his second son who died so young, and he wanted the piece of slag to be placed on his father’s grave. He became lost for words. It was the honest emotion of someone who had witnessed his father’s sorrow on a daily basis.]

- Kim Hoin (nephew of victim Kim Boojin)

(1) Background

Registered domicile: Anpyeong Township, Uiseong County, Gangwon Province

Current address: Same as above

Born: September 1937 (69 years old)

Other: His wife has passed away, and he lives surrounded by his children and grandchildren. He had one fifth of a hectare of farmland at the time of the interview.

(2) Background of the victim

Registered domicile: Same as the interviewee

Born: October 1923

Died: May 1941

Started work at the mine on September 24, 1940

Date and place of death: October 10, 1940 of sickness at the age of 18, two weeks after starting work, at the Uchigo Village shrine

Name of mine: Iwaki Coal Mine

Married in 1939 (son born in 1941, currently living in Uijeongbu, where he is a company employee)

(3) Interview background

Date: May 7, 2005

Place: Interviewee’s home (Family register confirmed the previous day at the town office)

Cooperation: Song Taegyeong and his wife Mutsuko Kofunaba (interpreter)

Interview content

I don’t know much at all about the time when my uncle was mobilized. My uncle Boojin’s wife, who married into our family from Kwon family, lived with us for two or three years, then she left, and their two children were raised by my father and mother, who are their uncle and aunt. I don’t really know about compensation, but I’ve heard that it was hard paying all the money for the older one of my cousins to go and fetch his father’s remains. Apparently, there was no compensation. [However, I got the impression that they were quite badly treated.] There’s no way for us to register a complaint with the current survey which the government is conducting to investigate the truth, because we have no proof. My father died 20 years ago and my mother 16 years ago. I was in my second year of elementary school when Korea was liberated, so I know nothing about those times. We have no clue what to do about it. What I want to say to the Japanese is that while I certainly have some resentment [I couldn’t pick up what he said next]. Ill-feeling towards the Japanese has seeped right down into my bones. Koreans were treated worse than dogs or pigs. What’s the point talking about it now? If there are documents in Japan, they should be put out in the public and Japan should pay compensation. I want Japan to acknowledge the facts by paying compensation. [This was according to the interpreter. I asked the interviewee to confirm that this was what he had said, but mild-mannered Hoin just nodded quietly.] My cousin who lives in Uijeongbu comes to visit his father’s grave once a year without fail.[viii]

- Ryu Inseob (eldest son of victim Ryu Deokcheol)

(1) Background

Registered domicile Geumseong: Township, Jecheon County, North Chungcheong Province

Current address: Wonju City, Gangwon Province

Born: 1931 (in his fifth year of elementary school when his father died)

(2) Background of the victim

Registered domicile: Same as the interviewee

Born: 1909

Died: April 1944

Cause of death: A mine cart went out of control

Name of mine: Dainippon Nakoso Coal Mine

Record: Disaster ledger section of Shutsuzou-ji Temple’s death register

(3) Interview background

Date: May 29, 2007

Place: Interviewee’s home

Family register: (moved to Wonju) confirmed during my first visit with the cooperation of the township office . Claim registration confirmed with the cooperation of the Verification Commission in Seoul the second time, leading to this interview. The interviewee already fully understood the purpose of the visit and I was very warmly welcomed. I was able to gain precious testimony in terms of understanding one aspect of wartime mobilization.

Interview content

My father was mobilized when I was in my third year of elementary school. He didn’t have any land so he tried his hand at various forms of commerce with little success. We think that he decided to become a “conscript” as a way of making some money.[ix]

My memory of the time when my father died (born in 1909, so at the age of 35) was that my mother and an influential relative went to fetch his remains and bring them home. I was in my fifth year of elementary school. My mother was farming a small plot of land and bringing up my three younger sisters, so she really struggled. She was older than my father and died at the age of 57 (born 1907).[x] Because my father applied to be mobilized as an “industrial warrior,” they made me write a “comfort letter” at school. My teacher praised me for it, saying that even though my family was poor, I had written a very good comfort letter, and the teacher put it up on the wall. Here’s my graduation register. After I graduated in the final year of the war, I worked for two years in the Geumseong township office. I had to quit due to circumstances, and worked in as a kind of public servant. I married my wife when I was 17.

Now I live on my pension and the money my four daughters send me, but my son died in a car accident, leaving behind my two grandchildren. [Ryu Inseob himself looks very good for his age and his mind is still sharp. He shifted to Wonju in 1978, possibly because Wolgulri, the village next to his native village of Seongnaeri, was also flooded due to dam construction in 1979. His stern character was doubtless due to helping out his mother at an early age and overcoming misfortune to make a life for himself. Through the interview, I learned that he was delighted that I had visited. I would like to continue cooperating with him to the greatest possible extent so that he can become a bridge for exchange with the people of Iwaki.]

- Choe Cheonok (younger sister of victim Senshoku Fumiyama)

(1) Background

Registered domicile: Seowon Township, Hoengseong County, Gangwon Province

Current address: Buron Township, Wonju City, Gangwon Province

Born: April 1936 (74 years old)

(2) Background of the victim

Registered domicile: Same as the interviewee

Born: 1922 (mobilized at age 22)

Mobilization period: December 3, 1943-July 16, 1944

Name of mine: Jōban Coal Mine (Aoba No. 4 West Dormitory)

Cause of death: Acute peritonitis

Noted in Sozen-ji Temple death register

(3) Interview background

Date: June 12, 2008

Place: Office at the city’s local administration bureau

Cooperation: Lee Minsong from the local administration bureau, Verification Commission local officer Lee Cheonghui

Interview content

At the time that my brother was mobilized, we were a family of five: my parents, my older brother and older sister, and me. There were originally six siblings, but two died, leaving just the three of us. In 1943 when my brother was mobilized, my cousin was apparently mobilized as well. I don’t remember anything about that time. I was only about eight, and all I can remember is that my brother was very affectionate towards me and used to carry me round on his back. I remember his face quite well. According to my cousin who survived, my brother was working as part of a unit of six. A cable snapped and my brother was squeezed by the coal wagon. He was badly injured and died a week after being hospitalized. I heard that my cousin sent home his remains, but I don’t know who brought them back.

There was no compensation money. We were sent a photo, but I burned it together with my parents when they died. My brother didn’t send any money back, but apparently he did send tobacco. After liberation, my parents were so depressed by his son’s death that he passed almost straight away. I was 18 at the time, so I got married and went to live with my husband. My husband was a good man and we had five children, but they’re all grown up and living elsewhere now. My husband died 30 years ago, and now I live alone.

The Association of Bereaved Families was set up, and they said that it wasn’t enough that money was sent; we needed to have it confirmed exactly which hospital my brother died in and how. So, the Association members and staff brought a court case. The first time they went to Japan I couldn’t go with them because I couldn’t afford the airfare. The second time, around 20 of us went over by plane. It was a big court, but I don’t know where it was or what it was called.[xi] [According to the List of Victims, her brother was in Aoba No. 4 West Dormitory. Looking at a photo from the time that Nagasawa Hide had preserved, tears came to her eyes. It was the first time that I discovered that people with a connection to the the Jōban Mine had already been involved in court cases like these.]

- Lee Sangrae (53 years old; nephew of the victim)

(1) Background

Registered domicile: Gunbuk Township, Okcheon County, North Chungcheong Province

Current address: Daejeon City

Born: April 1955

Occupation: Apartment manager

(2) Background of the victim

Victim’s name: Miyamoto (Lee Gwiseong)

Registered domicile: Same as the interviewee

Born: February 27, 1920

Died: December 17, 1942

Cause of death: Crushed by falling rock (death through serious injury)

Name of mine: Furukawa Yoshima Coal Mine (Matsuzaka Dormitory) Sakiyama(3) Interview background

Date: June 17, 2008

Place: Interviewee’s home (with his wife also in attendance)

Interview content

I don’t know anything about the time when my uncle was mobilized. I remember back when I was 10 that every single day, my grandmother (who passed away in the 1960s) would open up the main gate and cry as she waited for her son to come home. I didn’t know any of the details at the time of course, but I heard from the village head later on that my grandmother’s eldest, second, and third sons were all conscripted and, except for her third son Gwiseong, she didn’t know where they had gone, but the other two apparently escaped on the way and came home alive. I think my grandmother couldn’t believe that her son had died and just kept waiting for them every day.

In the recent government survey, I was able to tell them about my uncle and the village chief verified what I said, so I was able to put in a claim. [The interviewee was delighted that I had visited and listened intently to any information that I had about his uncle, perhaps out of feeling for his grandmother. It reaffirmed for me how important visits to victims’ families are in terms of the communication of parents’ feelings to their children.]

- Jeon Yunha (65 years old; youngest brother of the victim)

(1) Background

Registered domicile: Okcheon Township, Okcheon County, North Chungcheong Province

Current address: Apartment in town

Born: January 1943 (born on the day his brother died)

Occupation: Apartment manager

(2) Background of the victim

Victim’s name: Jeong Byeongha

Registered domicile: Gunbuk Township, Okcheon County

Address: Dejeong Township, Boeun County, North Chungcheong Province

Born: September 12, 1923

Name of mine: Furukawa Yoshima Coal Mine

Died: January 12, 1943 (aged 19 years and 4 months)

Cause of death: Loaded vehicle out of control, unnatural death in the mine (Choju-in Temple)

(3) Interview background

Date: June 16, 2008

Place: Interviewee’s home

Cooperation: Okcheon Township family register officer Oh Handwoo

Interview content

My brother apparently died the day I was born. At the time, aside from my brother, I also had my older sister and my parents. It was not only my brother, but my sister also died in the Korean War, and my mother became mentally disturbed and was run over by a train, dying in 1975. My family farmed in Boeun County.

An officer from the township office came to take my brother away. We were poor so he went to earn money, apparently. Someone went to fetch his remains, I don’t know who. I haven’t heard anything about travel expenses, etc. My mother’s grief was vast. And then she lost my sister, so she lost two children.

In relation to the Korean government’s project to uncover the truth, in April 2006, we were designated as a bereaved family, but I don’t know what happened after that. What do I think about the Japanese people and the Japanese government? My family was so poor that I couldn’t even go to high school. I work as an apartment manager now, but I also have to send money to my son. Life is very hard, so it would be good to receive victim compensation. Japan is a developed country now, so it has money. Given that it forced Koreans to work back then, I think it has to pay compensation to the children and grandchildren of those workers now for their living. The successors to those mines should pay compensation. When my brother died, the family register names Ōta Hiroshi as the person giving notification of his death. I want someone to do a search and find out what happened.

[In the record for Jeong Byeongha in the family register held by Okcheon Township, it says “(Partly unreadable) No. 1200 …… (unreadable) …… South electric car pit, No. 1 new sloped pit, Furukawa Ypshima Coal Mine, Ooaza Kami-Yoshima, Yoshima Village, Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture . (unreadable)……Ōta Hiroshi.”]

- Interviews with family members of deceased mobilized workers who returned to Korea

- Kim Juchan (78 years old; son of deceased mobilized worker Kim Seonbong)

(1) Interviewee background

Address: Oksan Township, Cheongwon County, North Chungcheong Province

Born: 1930

(2) Background of the deceased mobilized worker

Name: Kim Seonbong (Seonbong was his official name registered in the family register; he was usually known as Jeongman)

Registered domicile: Same as interviewee

Born: 1900 [Group violence incident] [Accused]

Age at the time of mobilization: 43 (April 1943)

Mobilization period: Around 1943-April 1946 (when Kim Juchan was 18)

Name of mine: Furukawa Yoshima Coal Mine

Died: 1948 (after returning to Korea; died in an accident when Kim Juchan was 23)

(3) Interview background

Date: June 4, 2008

Place: Interviewee’s home

Cooperation: Yun Chonron and Park Jongan from the Cheongwon County local administration division; Sin Imseon (translator) from the Cheongju County trade and economy division

Interview content

If you ask me, how my father was mobilized, one day while he was eating a meal, he was ordered to go to the township office. He went out but didn’t come back. At the time, I was living together with my father and my uncle (younger brother of my father). After my father was mobilized, my uncle too was immediately mobilized to Hokkaido, so I was left by myself and had to go to live with another family and work. My father sent back between 10 and 20 yen every single month. He didn’t drink at all. The money was sent to the post office in Ochang, and I remember that the notes had a special smell. I saved the money he sent and bought some land—1,000 tsubo [almost an acre].

There was talk about my father rebelling against the company. I heard that he was beaten almost to death at the police station. He rebelled because the overseers were very strict and always on people’s backs. They were also quick to hit people and allowed no freedom. I didn’t hear anything about disabilities as a result of his being beaten at the police station. After he came home, he talked at the local community center and other places about having rebelled. He had a good sense of humor and would talk about how nice Japanese women were. He was really good at singing, and people would get transported away just listening to him. He was particularly good at folk songs. He was small and thin, but he wasn’t the kind of person who was quick to start a fight.[xii]

After liberation, my father said that he had 30 yen but spent all of it on the way home. He said that they always ate a good bellyful of white rice at the mine. He felt that on an individual basis, all the Japanese were good people. They just had issues in their emotion.

- Analysis of surveys and testimonies

(1) Lifestyles and feelings of bereaved families of those who died during mobilization

(a) The motivation for conducting these interviews in Korea arose from a report written in Ariran Tsushin [Ariran Bulletin] No. 22 by Son Daeyong from the Shimotsuke Choson Issue Study Group on the Korea Issue in Tochigi Prefecture, as well as a field study report on the Kishu Coal Mine, which inspired me to search out the families of those victims of mobilization (in Korea, they describe them as “people who died at the site”) in case their registered domicile was known. Utilizing advice from Jeong Hyegyeong on how to conduct such a survey, I started by considering the exact purpose of the survey, and decided to focus on commemorating the victims and thanking their families for the mobilized workers’ service. That sentiment remains the same today.

(b) According to Shigeru Nagasawa, 296 mobilized coal mine workers died in the Jōban Coal Field as known today. The first step in my survey was to take this List of Korean Miners from the Jōban Coal Field in Wartime Dying in the Performance of their Duties and organize it into provinces and counties in Korea, and then, armed with a slightly revised list of the deceased, to visit those provinces which had the most victims. I was generously assisted by officers in charge of family registers in the various towns and townships, as well as some dedicated local volunteers.

The Circle for Peace Discussion which backed the survey is a community hall group which has operated for the last 20 years, studying local scars of war particularly in the Iwaki-Nakoso area and holding war exhibitions for the purpose of peace education. In recent years, in connection with the damage done to Asian people, they have been looking at Koreans mobilized to work in the area during the war, also providing full cooperation to the Sakhalin Double Recruitment Mission and visits to Japan by bereaved families through the mediation of Shigeru Nagasawa. The organizer of my survey is this Circle for Peace Discussion, and it is now considering hosting former mobilized workers and bereaved families.

(c) So far, I have discovered the names and whereabouts of bereaved families of the total of 18 victims who died during mobilization, including eight people that I interviewed and 10 people that I identified through family registers and telephone calls. Including the three people whom I interviewed who had a mobilized family member who had returned to Korea and died afterwards, I have found information on 16 people. Here I report on the circumstances of the former mobilized workers and the bereaved families, focusing on the eight people that I interviewed.

In terms of the bereaved families, most were the daughters (five) or sons (two) of victimes, while four were nephews, three younger brothers, one the father, and one the grandchild. One person refused to be interviewed, and one was lost. There were no victims whose wives were still alive, so unfortunately I couldn’t ask those who suffered the most at the time about their experience. When I spoke on the phone to the grandchildren, most knew nothing about the time when their grandfather died.

(d) My first family register study was conducted in Namwon and Hamyang, while for the second, I bothered family register offices in a dozen or so towns and townships with survey requests sent by post. Through their cooperation, I identified another four places in addition to Namwon and Hamyang: Uiseong Township,Uljin Township, Jecheon , Okcheon Town. The significance of the family register surveys was that in the case that records remained from the time when Korea was under Japanese rule, they provided an important source of information in terms of learning the name of the person who had notified the death locally, and also their families. Where a specific registered address was recorded, I was almost always able to find a victim by looking at the list of names removed from family registers. In places like Gangwon Province where the Korean War was particularly fiercely fought, the original records were in many cases lost and the survey work was difficult. The Tochigi Prefecture postal survey apparently produced a very high response rate, but in the 2007 survey, I was even sent a warning that if I was not a family member, I was to go through the embassy in order to protect privacy, which presumably means that it isn’t possible to find out what happened to wartime victims if the government or the actual parties don’t want you to.

(e) In the case of married victims who had owned their own land, the wife often seems to have supported the children through farming, but in the absence of land, the wife generally obtained a divorce and left her husband’s home, with the children brought up by their grandparents. Children who were old enough to go to elementary school remember writing and sending comfort letters to their fathers. I was unable to interview two of the daughters because they couldn’t meet with people either because they were living alone in their old age or in a facility. They had also been unable to register a claim in the government’s latest survey. Another daughter had registered a claim in the survey conducted by the Park Chung-hee administration and had received money as a reward for her father’s services.

Where the victim was single, there was no one to tend their grave so they have effectively disappeared. It was heartbreaking to hear from bereaved families—nephews and younger brothers and sisters—about the grief of parents who had lost their child at a young age. It was clear from the stories I was told—memories of a father who died young as a result of his son’s death; of a grandmother who opened the main doors to the street every evening waiting for her son to come home; of a kind older brother who used to carry his little sister on his back—that the victims live on in the hearts of their families even now.

(f) Finally, in relation to the return of remains and compensation and assistance for victims, in the case of someone who had died while in public service during the private recruitment period it was supposed to be set down in the miner assistance regulations of each mine; during the official mediation period in the Labor Service Corp assistance regulations (Rules on Support for Labor Service Corps Members, etc.); and during the outright conscription period in the rules on national conscription assistance.

In the case of Kim Boojin who died in hospital 10 days after he was mobilized to work at the Jōban Coal Mine during the private recruitment period, the bereaved family did not receive so much as travel expenses to fetch his remains, something which continues to rankle with them today. However, most families that I spoke with had fetched home the remains, and it was unclear what the circumstances were that prevented other families from taking home the remains of the three bodies still left in the city (of Iwaki) and more than 20 bodies that were repatriated to Bogwangsa Temple in Paju. I was not able to identify the single body stored at Zuiho-ji Temple in my family register survey. In the case of Park Soobok, who died of chronic pneumonia and whose remains are stored at Ganjo-ji Temple, I was able to confirm that the address of his younger sister, who had moved from Ulsan to Gyeongju, which could be said to be a result from the Verification Commission’s current survey.

(2) Interviews with survivors who returned home

(a) Summary of interviews with former mobilized workers who returned to Korea

In most cases where I was able to find those who were mobilized to Jōban Coal Mine and are still alive today, it was thanks to cooperation from the Commission on Verification and Support for the Victims of Forced Mobilization under Japanese Colonialism which the Korean government set up in 2004. The task would have been impossible without help from Survey Division No. 1, later to become Survey Division No. 3, as well as its local officers. Particularly for the third survey, they spoke by phone to 44 of the 249 survivors from Fukushima Prefecture who are still alive today and who had registered wartime mobilization damage claims, and, thanks to their help, I was able to interview nine of them in person. It was greatly meaningful that, over my three-week visit, during which time I also investigated the group violence incident and met with bereaved families, I was able to meet with six of the former mobilized workers and speak with them directly.

Han Gwanghui, the first former mobilized worker I interviewed during my first survey, was one of the 293 who registered for wartime mobilization damages as part of the system just set up by Hoengseong ’s local administration division, had worked in the Jōban Coalfield, and had agreed to be interviewed. He worked as a mobilized wokrer for over two years in the Furukawa Yoshima Coalmine, the second biggest in the area. His account paints a vivid picture of the actual state of forced transport during the official mediation period and the whole process from labor and treatment of the workers to liberation, and the return home, as well as touching on the feelings towards the Japanese.

My interview during the second survey with Lee Chilsong, who was mobilized at the same time, was held on the condition that it was not to be published, but because of the very valuable content, I have reported just the content but under a fictitious name. In particular, the mine’s boast of being a superior mine, “the best in East Japan,” is partly reflected and forms the basis of his testimony about it being a “model mine.” In that sense, it should be noted that there seems to have been something behind the appointment of conciliatory labor management. It was also the first time that the route by which mobilized workers returned home was revealed, which was extremely valuable.

The experience of Song Gabgyu, who worked for more than three years at the Dainippon Nakoso Coal Mine, the third largest local mine under the Coal Control Board of the local minces, was described vividly, with the names of local places as well as Nakamura Hanba, which was known locally as a Korean dormitory, slipping easily off his tongue. Respiratory diseases which look like aftereffects will be the subject of a further study, but are highly likely to be pneumoconiosis (lung disease caused by dust inhalation). The beginning of self-organized repatriation after liberation also merits attention.

Lee Heungsun was mobilized at the end of the outright conscription period and did not work in the mine for long, but he identified himself wearing traditional Korean dress in a photo commemorating a new round of Korean miners joining the mine, and his experience was invaluable as one of the 60 fresh-faced “ōchōshi” [Translator’s note: literally, “men who responded to the call for conscripts”] who came from Hongseong County.

Next, I found another two men this time who were also mobilized to the Furukawa Yoshima Coal Mine, making up a total of four interviewees. Kim Changwol escaped after just over two months. He lived in the same neighborhood as Kim Seonbong, the oldest among the accused of the group violence incident, and they apparently knew each other well. Despite being 84 years old, he was very spritely, so I should have the chance to talk to him further. My meeting with Kim was the result of the great efforts of the officers of Cheongwon County’s local administration offices as well as the Verification Commission.[xiii]

Jang Gyubok from the Furukawa Yoshima mine is now living happily amidst his grandchildren in rural Gyeonggi. His memory of being kindly treated as the electrical mate in the mine and of being returned home as a result of a conscription examination made his experience at the mine somewhat unique.[xiv]

Ryu Bongchul, who was mobilized at the Iriyama and Jōban Mines from the private recruitment period almost right up until Japan’s wartime defeat, was fatherless and lived just with his mother and older brother before he was mobilized, and because of his young age, he was apparently protected at the mines by older men from his hometown. He came home in January 1945. Due to his long mobilization stint, when he was shown photos of the dormitory entrance ceremony, he remembered them well, providing very interesting testimony that included his association with the Japanese.

The last on my list of surviving mobilized workers, Jeon Byeongryong, lives in the mountains behind Girin Township in the upper reaches of the Bukhan River. The interview was made possible with the kind cooperation of a Girin Township public servant. Jeong was almost spitting out his words when he said that he had not a single good memory. He was mobilized to the Iriyama and Jōban Mines during the official mediation period. The Verification Commission had him down as going to the Furukawa Yoshima Coal Mine, but from his testimony, he appears to have been mobilized to the Iriyama Coal Mine in August 1943 as one of the 100 men “supplied” from Gangwon Province.

I spoke by phone to one other of the nine former mobilized workers to whom the Verification Commission introduced me in Nonsan and Muju, but I couldn’t get my intentions across and he refused to be interviewed. I was able to meet with Mr. Meng from Gyeongju, but because of the aftereffects of a car accident, he wasn’t in a state to be interviewed. In Muju, I was fortunate to have interpreters supplied by the county government in Muju, and in Cheongwon by Cheongju City. My heartfelt gratitude also goes to all those who kindly lent their assistance in communicating the meaning of my clumsy Korean.

(b) Analysis of interviews with wartimemobilized workers who returned to Korea: Forced transport

Looking at the forced transport aspect of mobilized workers in the case of those whom I visited in the course of my three surveys, of the eight survivors, one was mobilized during the “private recruitment” period, five during the “official mediation period,” and one during the “outright conscription” period. Seven of the former workers gave testimony concerning their time as mobilized workers, of whom the earliest, Ryu Bongchool (October 1941), was mobilized during the private recruitment period. He reports being “captured” by police and local officials, with his recruitment clearly forced. He was also not returned home even when his mother passed away on the grounds that he was only the second son. One hundred men were also taken from Muju to the Iriyama Coal Mine in February 1942 (I am currently surveying those who completed their full term). Next, the cases of Han Gwanghui and Lee Chilsong, who entered the Furukawa Yoshima Mine in June1943 during the official mediation period, were typical of the way that workers were taken during that period. Han had recruitment officers together with the township’s secretary and powerful members of the hamlet show up and block the entrances to his house, and was taken away from there. In Han’s case, as well as that of Lee, who agreed to go because he was worried about the possible impact on his family of the demands made in the repeated conscription notices he received, administrative measures and social coercive power were used to mobilize them with no chance to agree or disagree. In Jeon Byeongryong’s case, despite being the eldest son, he was apparently told that if he escaped, his father would be dragged out instead of him. He was taken away by the district head, the local police, and township public officials.

Lee, who was taken during the outright labor conscription period, notes that violence was used. Coerciveness was an element of mobilization common in all three periods. At this stage, I cannot identify any regional characteristics in terms of the time of mobilization.

(c) Forced labor

Indexes in terms of examining the forced labor aspect include “whether the freedom to choose the type of work,” “the freedom to take breaks,” “the freedom to go out and to use telecommunications,” and “the freedom to quit” were restricted by “physical violence” by labor managers or by police force.